The Liquid Gravity Model (LGM):

A Physically Intuitive Approach to Atomic Understanding

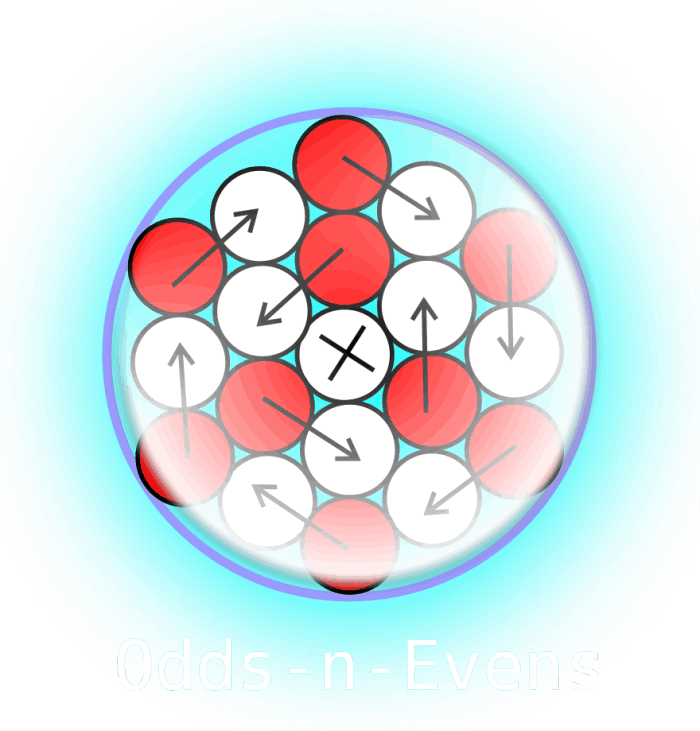

The Liquid Gravity Model (LGM) presents an innovative and intuitive framework for comprehending the intricate processes occurring within an atom. By likening nucleons to liquid-like droplets, the model provides a tangible way to visualize atomic behavior and dynamics.

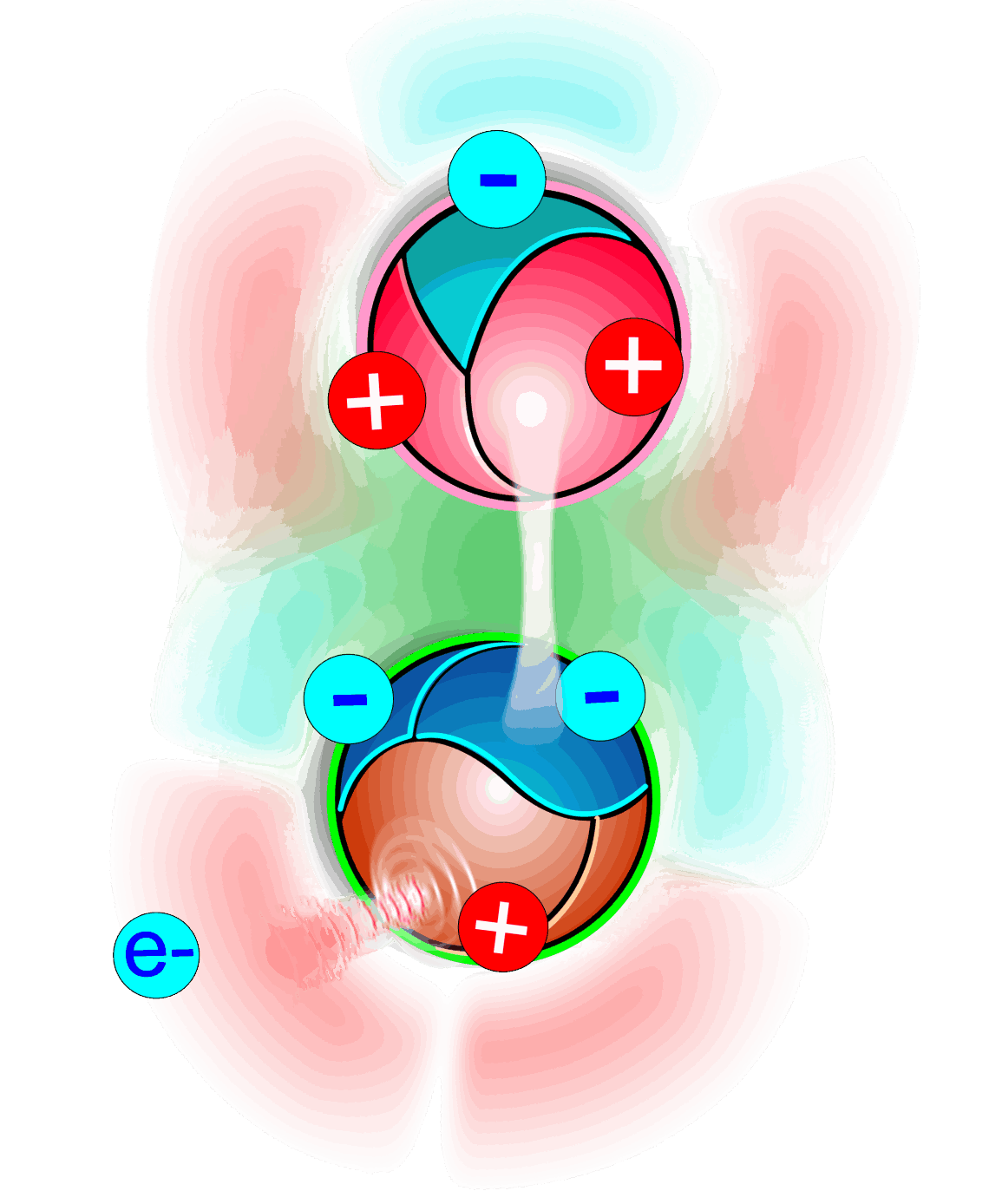

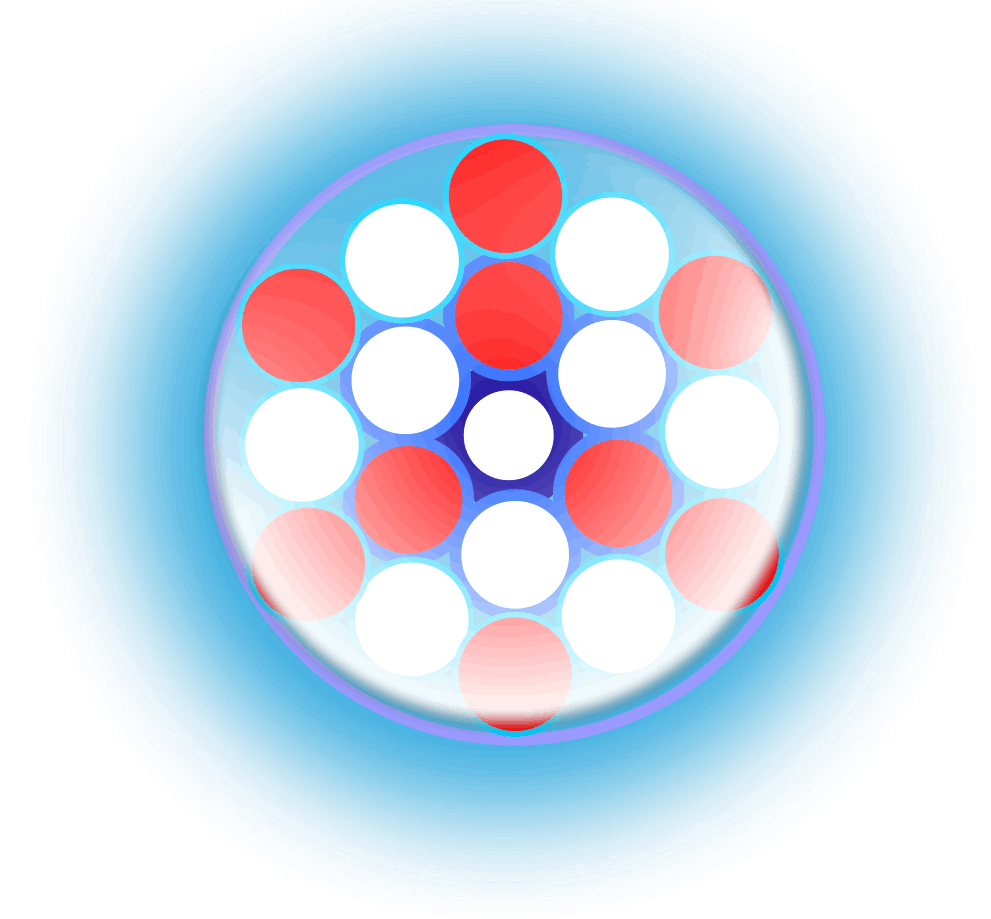

The Concept of Nucleons

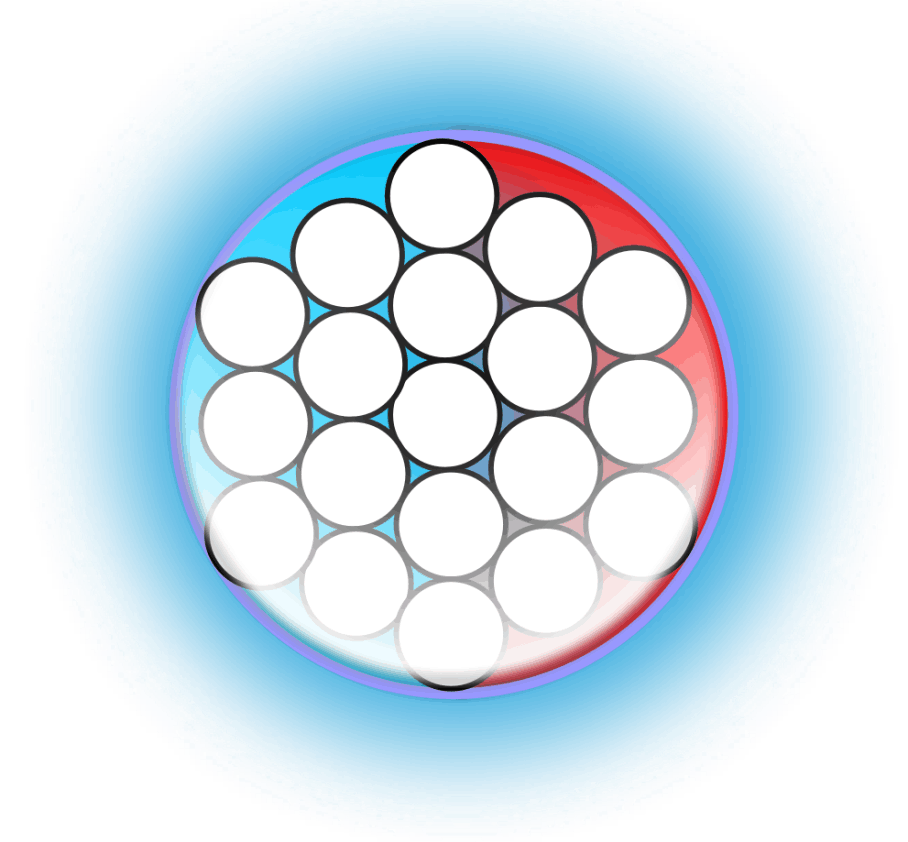

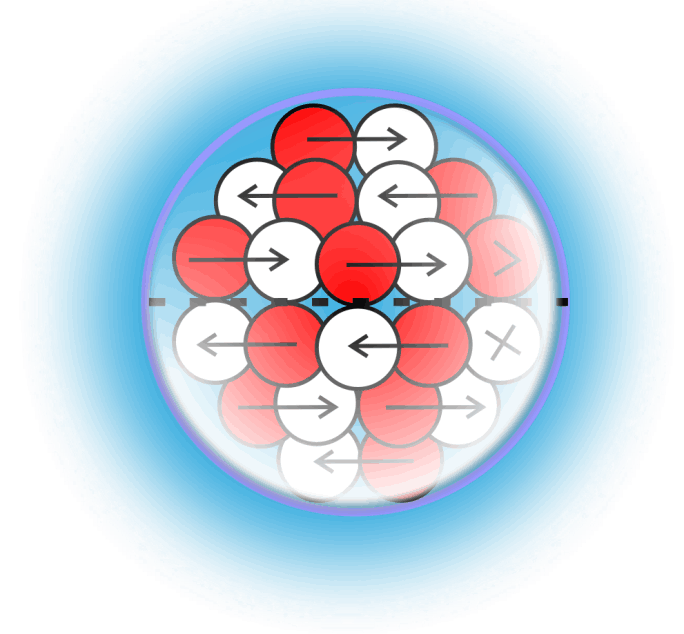

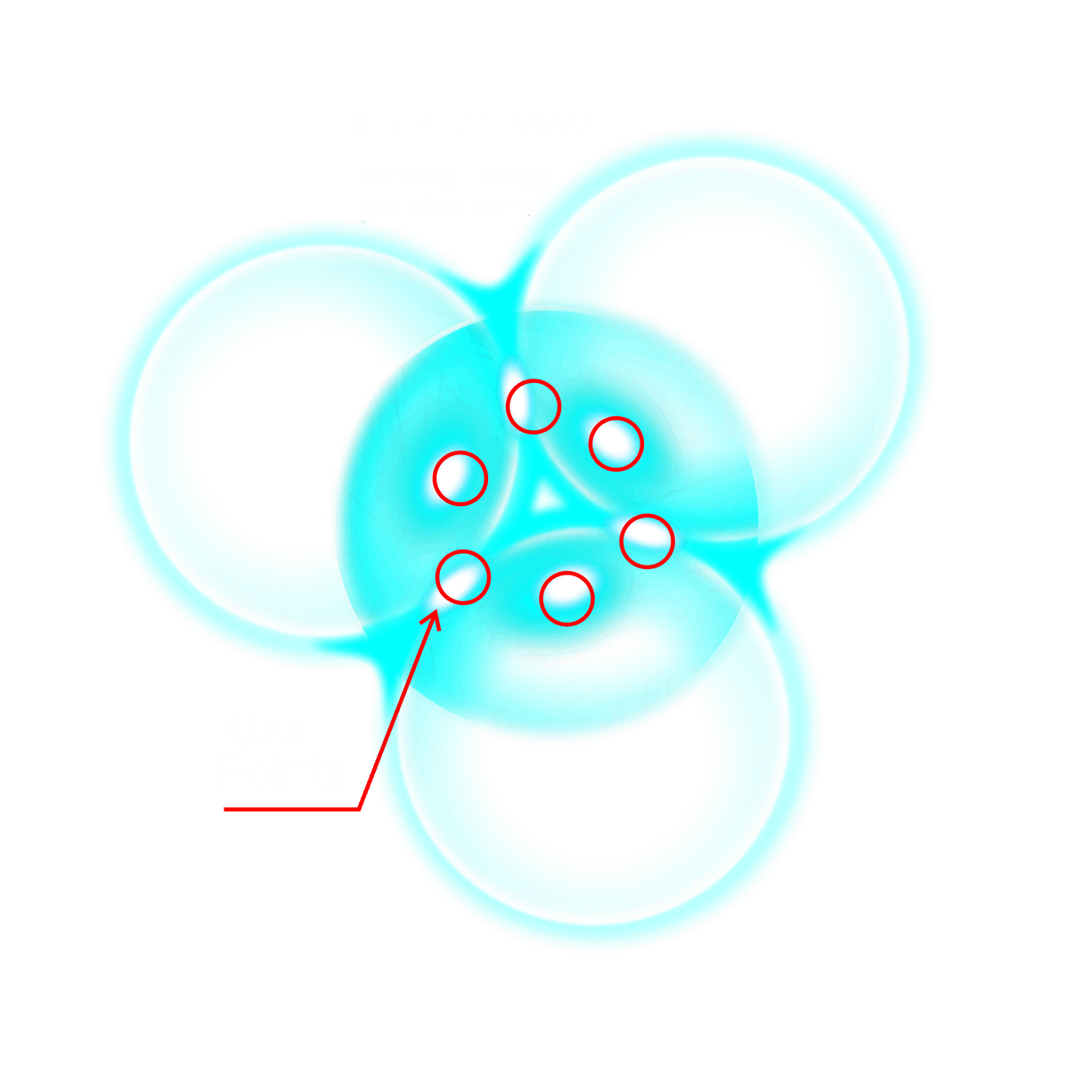

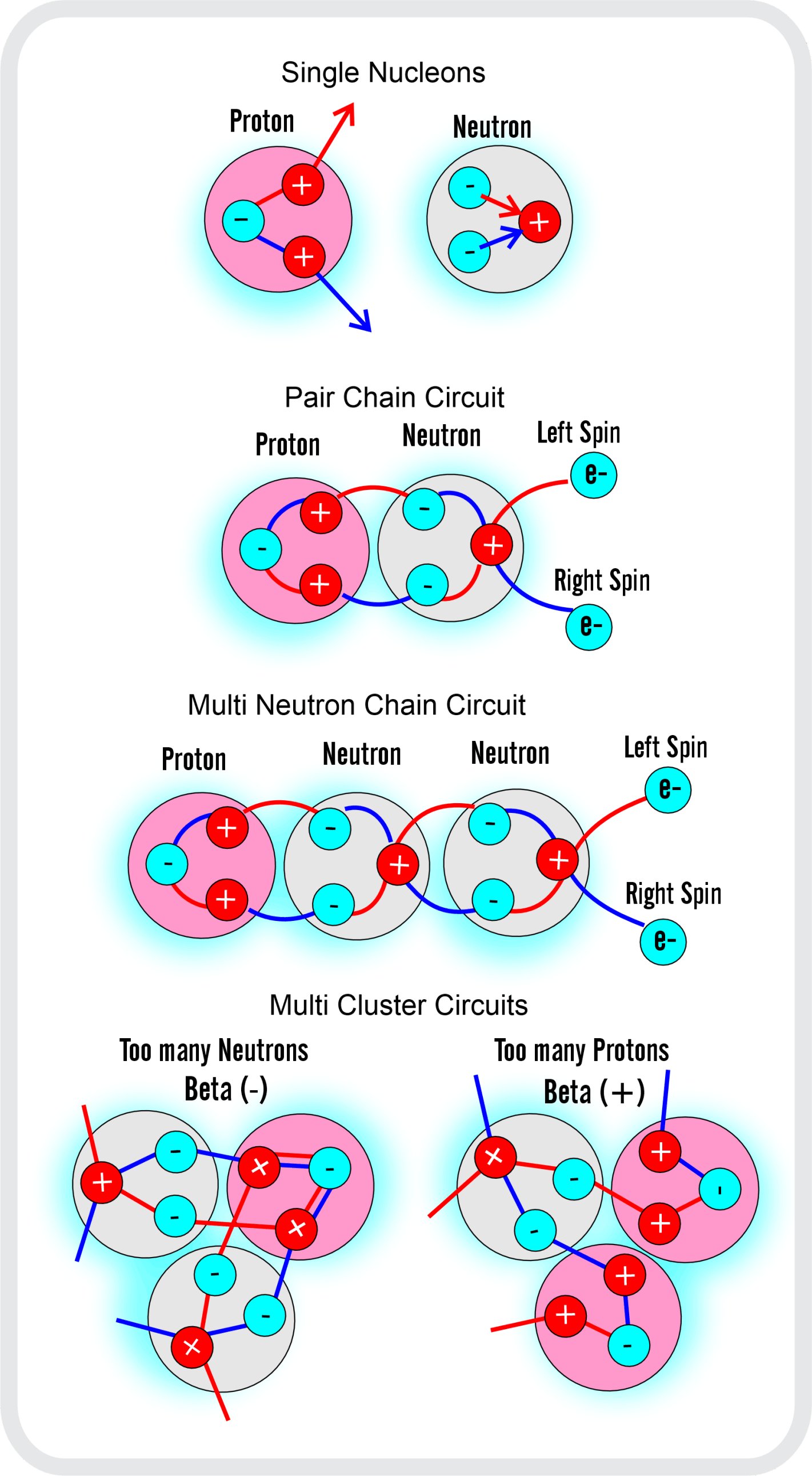

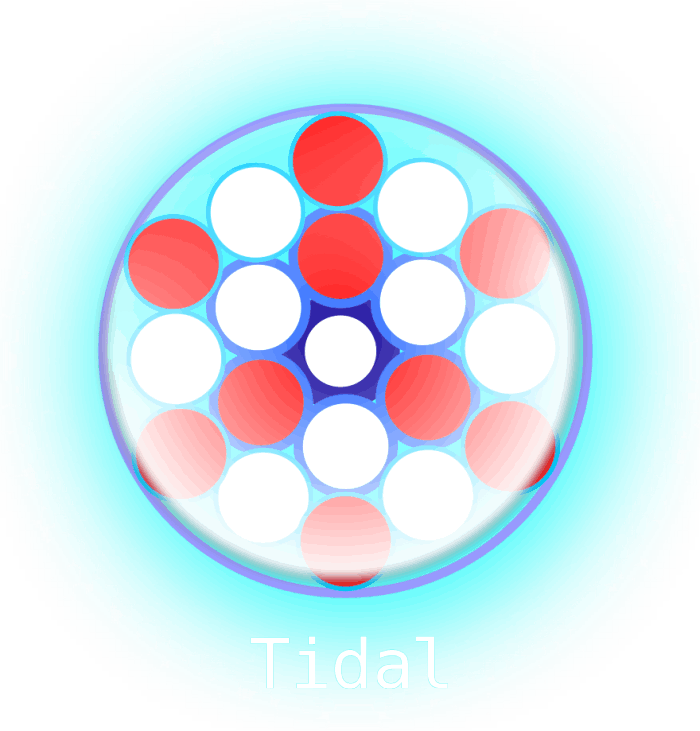

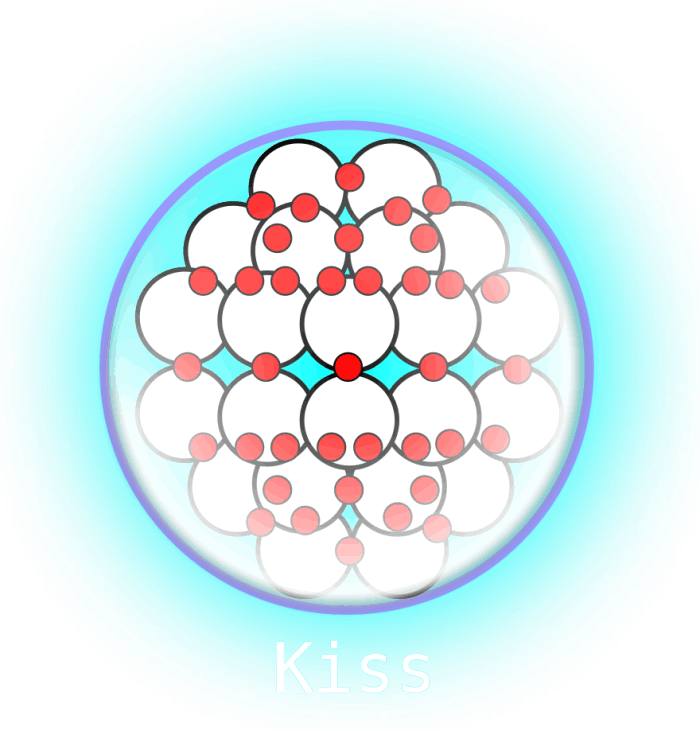

In the LGM, nucleons (protons and neutrons) are conceptualized as droplets filled with a pulsating wave. This unique perspective enables the formation of dynamic vortex structures and eddies within the atomic environment. These liquid-like properties offer a fresh lens through which to examine the connections and interactions between nucleons, enhancing our understanding of atomic mechanics.

The Atomic Engine: Properties and Rules

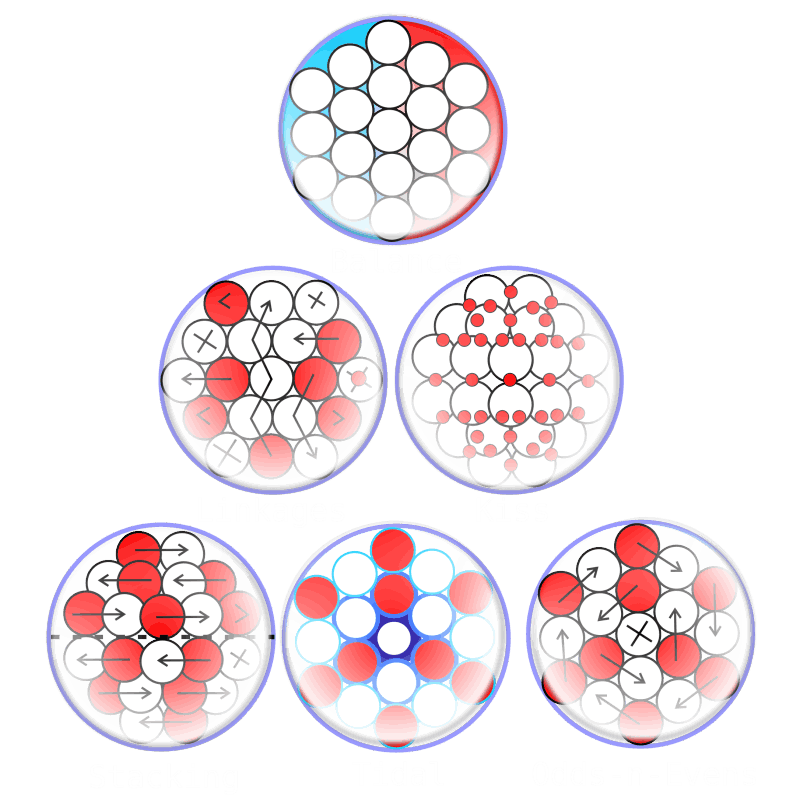

The LGM serves as an "atomic engine," delineating various properties and rules that govern atomic structure and behavior.

Key components include:

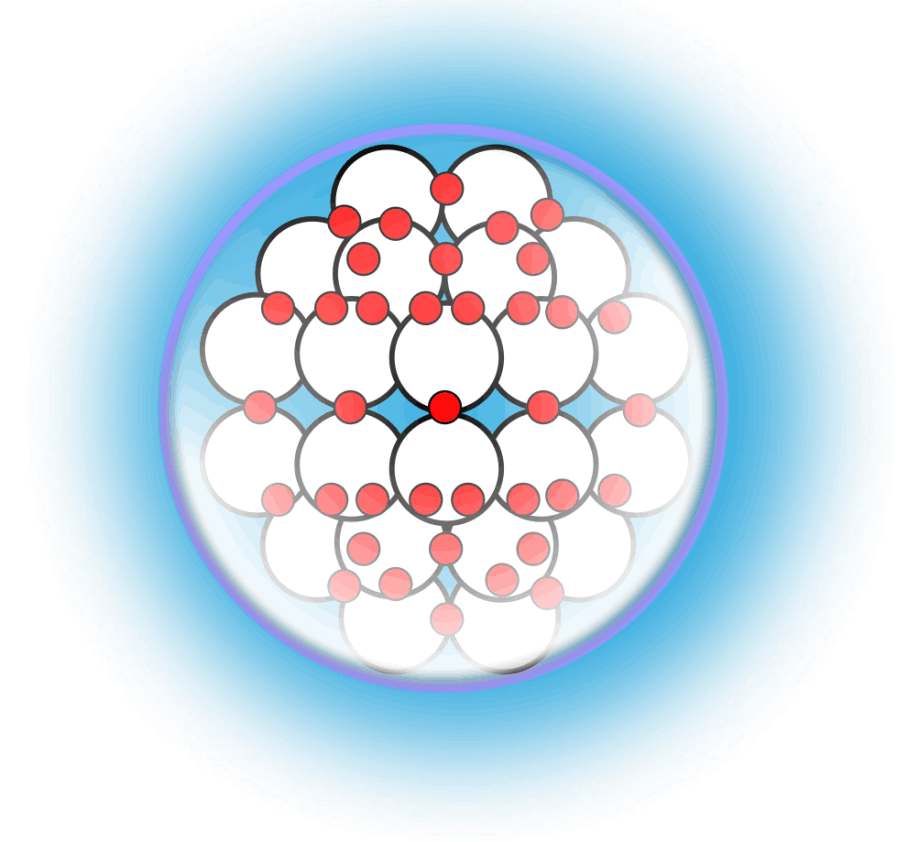

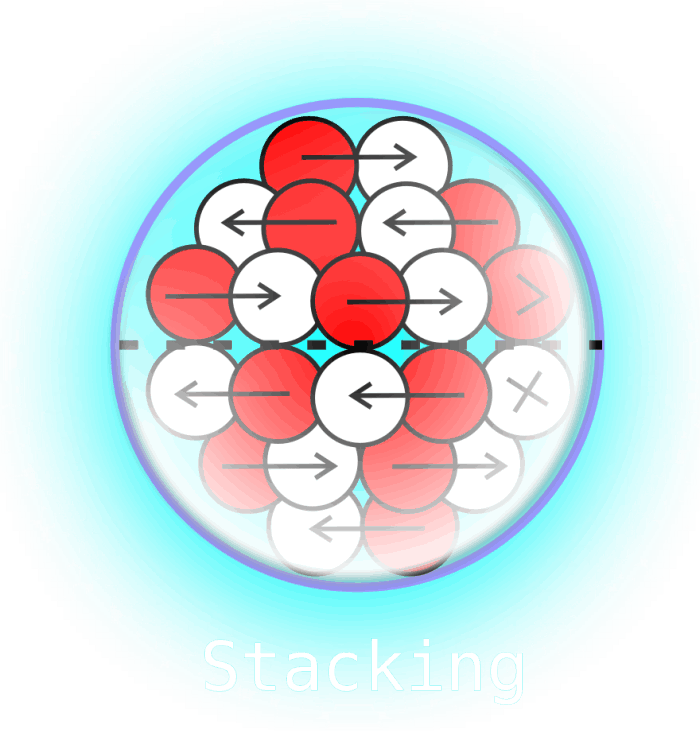

Proton and Neutron Connections:

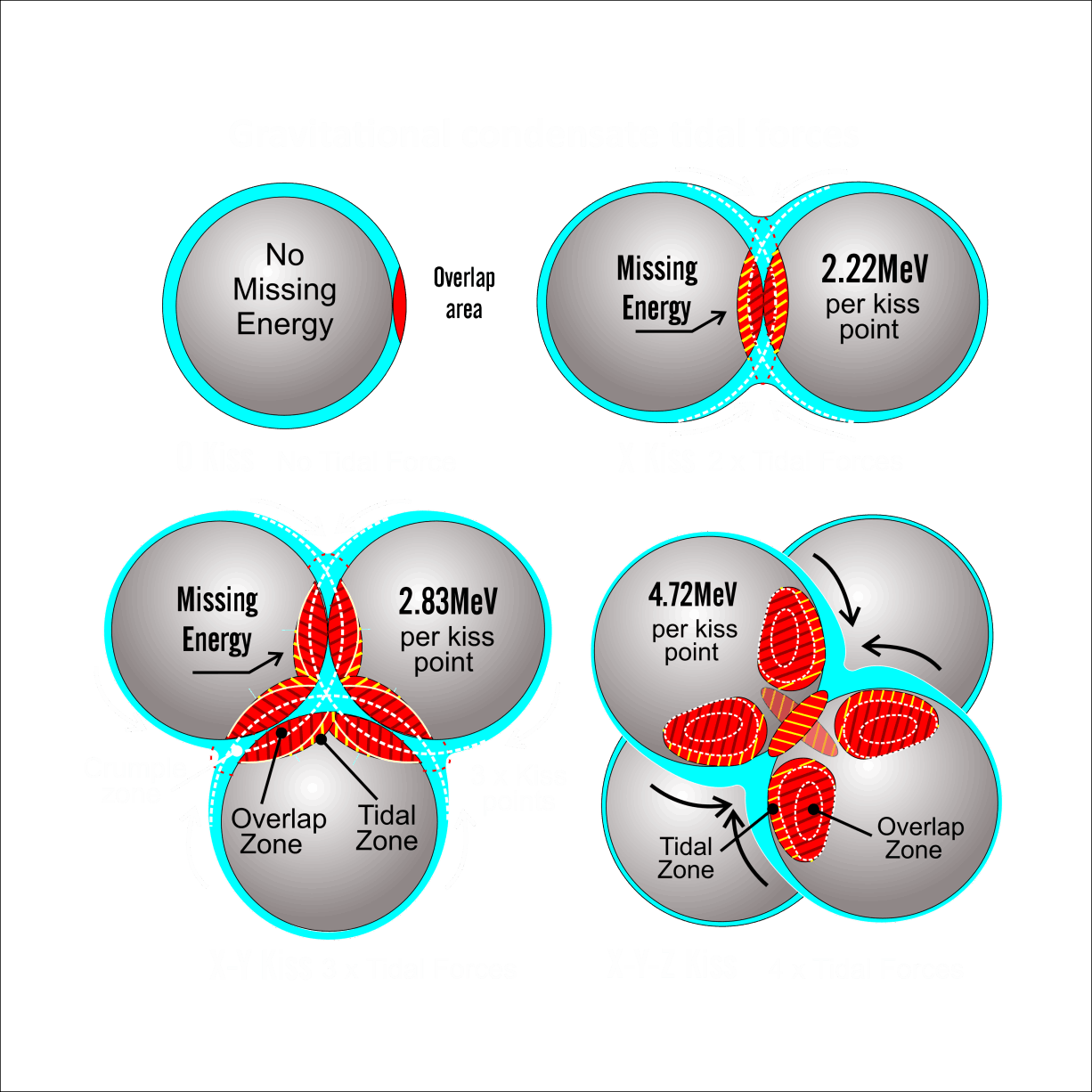

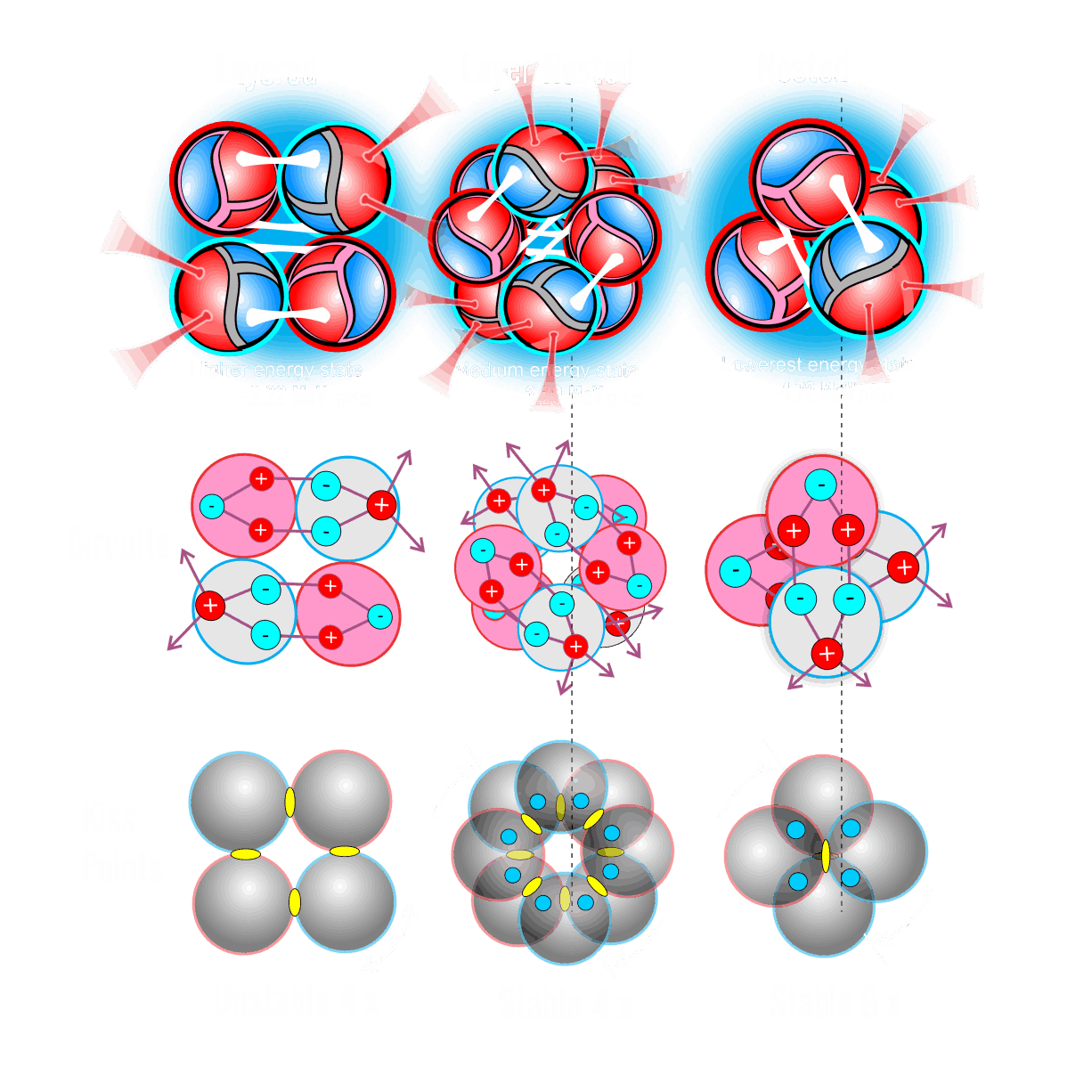

The relationships and bonds formed between nucleons are crucial in defining the stability and structure of atomic nuclei.

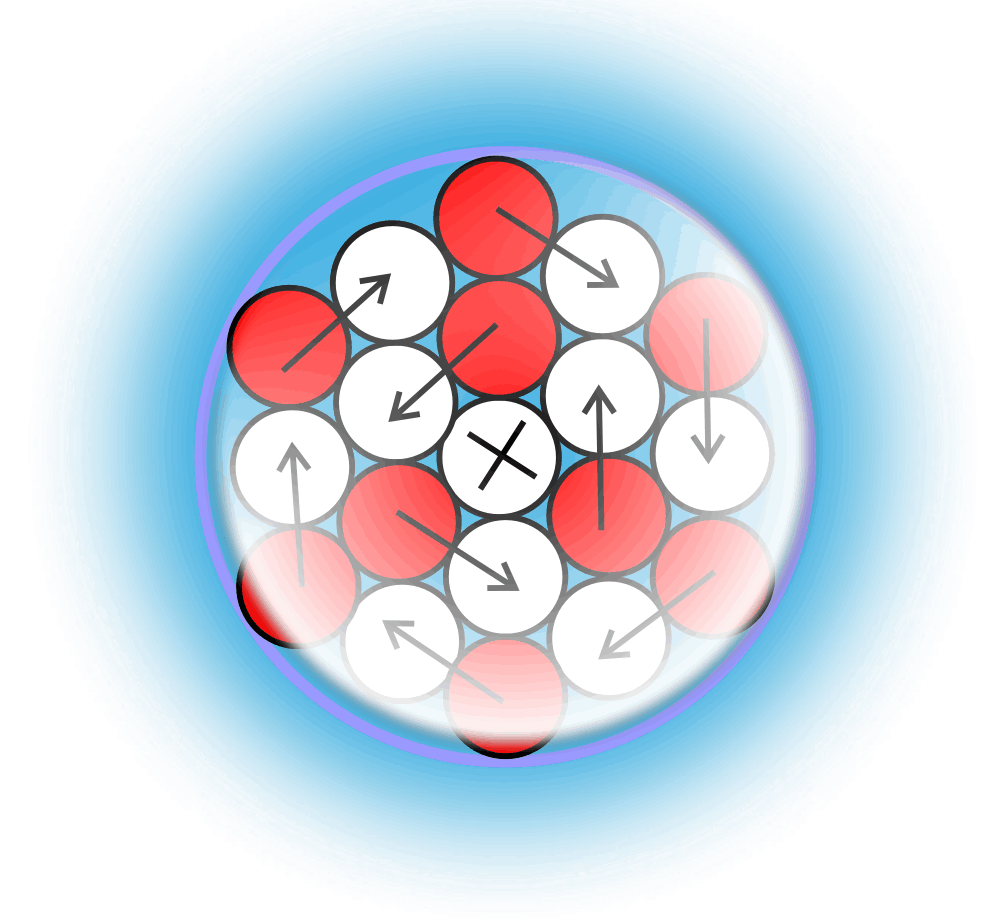

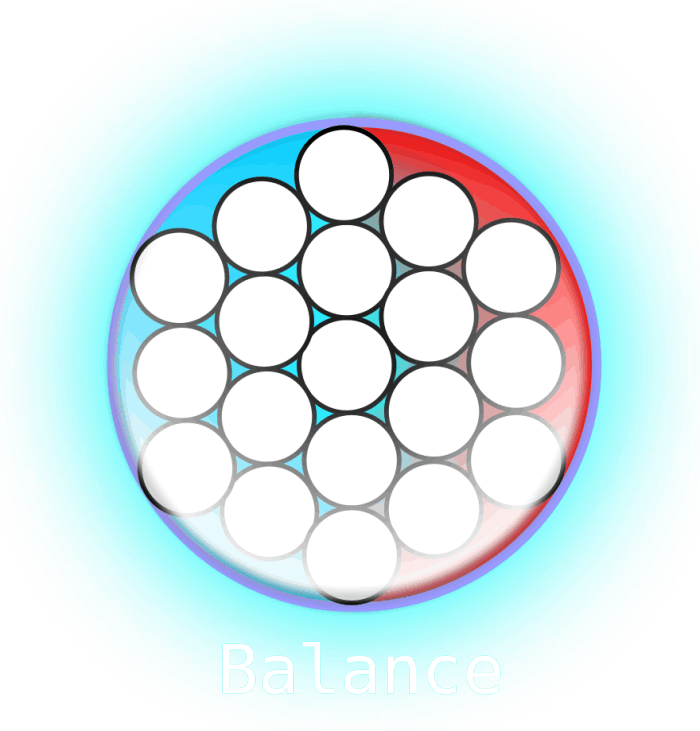

Nucleus Structures: The arrangement of nucleons within the nucleus plays a vital role in determining the characteristics of elements and their isotopes.

Decay and Instability Triggers: Understanding the factors that contribute to decay and instability is essential for predicting the behavior of atomic nuclei.

New Discoveries: Uncovering Exciting Explanations

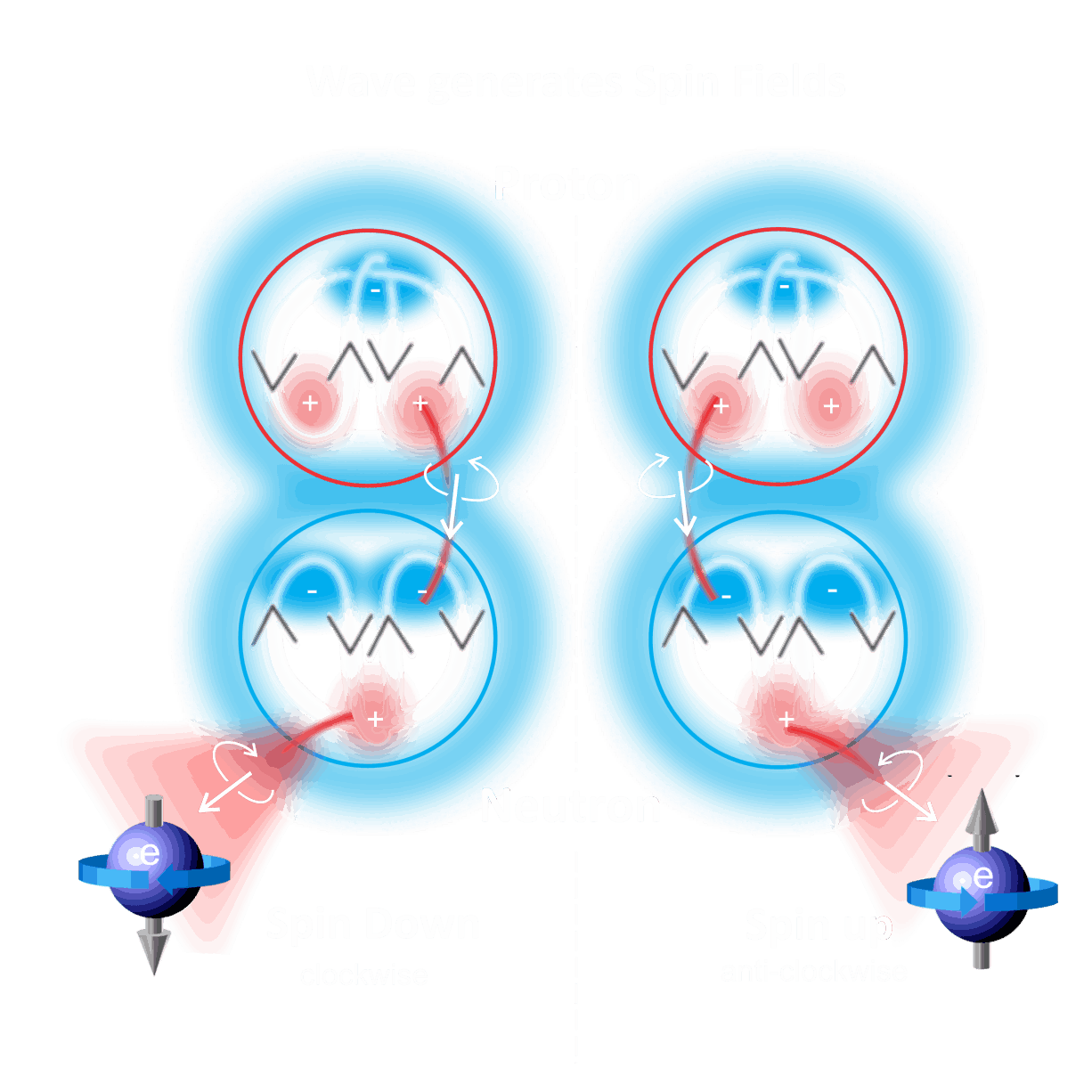

One of the most thrilling aspects of the LGM is its capacity to explain previously enigmatic phenomena, such as electron half-spin.

Also identifying the elusive realm of quantum gravity and how it plays a key role in the nucleus.

By bridging gaps in existing quantum theories, the LGM aims to provide clarity on these complex topics.

Testing the Model

The LGM employs six distinct properties to calculate binding energies, demonstrating significantly improved results over the traditional Liquid Drop Model. This advancement in accuracy not only reinforces the validity of the model but also opens avenues for further research and exploration.

The Goals of the LGM

Ultimately, the Liquid Gravity Model aspires to demystify the quantum world. By enhancing our understanding of atomic interactions and stability, the LGM seeks to identify the concept of "Stability Island"—a metaphorical safe haven of stable atomic configurations.

In conclusion:

the Liquid Gravity Model represents a transformative approach to atomic theory, offering a physically intuitive method for grasping the complex dynamics of the atomic world. As research continues, the LGM has the potential to redefine our understanding of atomic behavior and contribute significantly to the fields of quantum science and physics.